A

Journey Out Of Madness

by Ed Ott

For almost thirty years they had been hidden away: Sixty-four serigraphs, hibernating

in four flat black boxes, waiting for me to come to terms with my obsession

and ultimate madness around their creation. My children grew up knowing that

these boxes contained some beautiful images that I had once printed for some

artist, but little else. I rarely talked about them. When I did, it was always

with an undercurrent of sadness; a sense of something huge that I had accomplished,

but then stumbled, greatly, in the process of creating them. I'd let this project

consume my life so completely, and for so long, that I ended up in a mental

hospital, exhausted, depressed, and utterly convinced that what I had done was

a failure.

The year was 1980 and I was just finishing a course of study for my BFA at Arizona

State University. I was getting my degree in graphic design, with a minor in

serigraphy. Design was my focus, for practical reasons, but screen printing

was my love. With it I could make many copies of my image, enough to sell or

trade with other artists. The university had a great printmaking department.

Within it was the serigraphy studio, where I spent most of my extra time. I

invented a simple technique for registering deckled paper with precise consistency.

I taught other students, and faculty members, how to improve their editions.

It was with great love of this process that I became an expert. With serigraphy

I had found a home for my obsessive behavior.

When I graduated I was offered a unique project: I'd be paid to build a printmaking

studio, near the campus, and print an edition of serigraphs for Sandra Hall,

a Southwestern artist, which would be called A Journey of the Spirit.

In the realm of academia, the offer was a coveted opportunity; an internship.

It was a collaboration with some great creative minds from the diverse fields

of papermaking, printmaking and graphic design. I saw this as a rare opportunity

at leaving my mark in the field of in fine arts. Being a printmaker was much

more exciting than being a graphic designer. I'd just graduated at the top of

my class and I was ripe for the unique challenge that lay ahead. I seized the

moment and signed the contract.

Much was required of me as the printer for Sandra's vision; I had to print hundreds

of different multicolored blends with precise consistency and registration,

many thousands of times on seven thousand of sheets of 30x44 hand-made paper.

I'd be working on four images at a time, which would require careful planning

and precise preparation. My biggest challenge would be the blends; I had to

print as many as ten colors at a time and hold those colors in place for 315

impressions. The edition would be 250. There was little room for me to make

mistakes. In hindsight had I the slightest inkling of the immensity of this

task, and the sacrifices required from me for the next twenty seven months,

the Journey would not exist. I grew to understand the aphorism “ignorance

is bliss”.

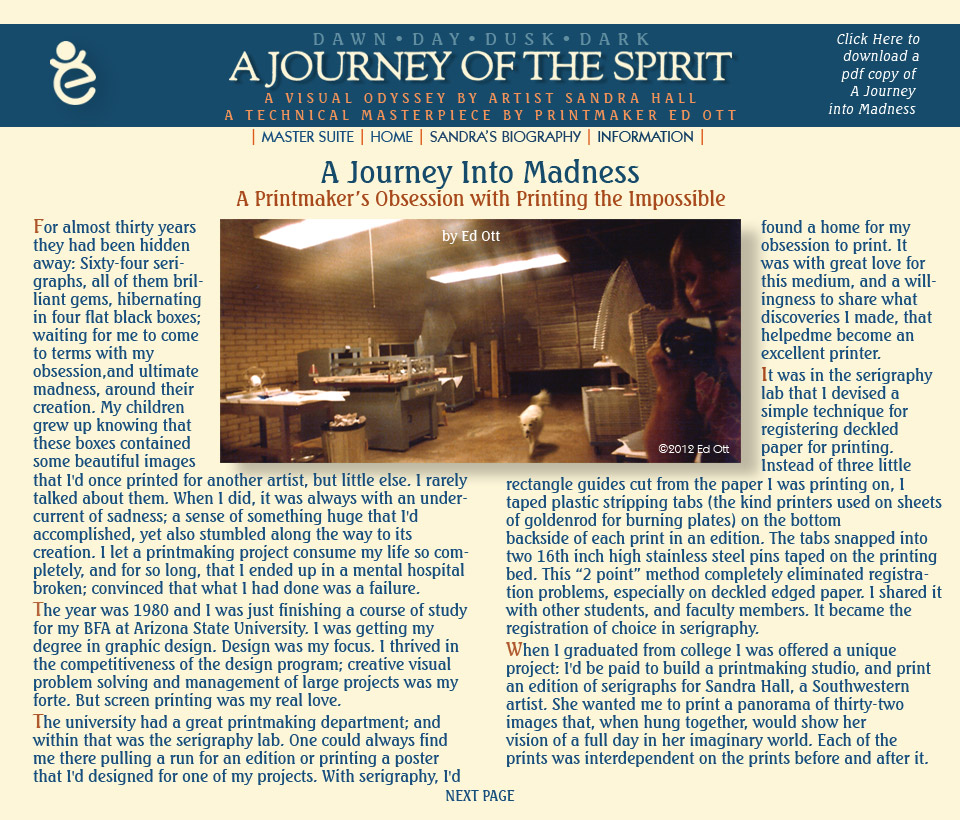

Building the printmaking studio was my first task after signing the contract.

With a limited budget, I relied on my creativity and innovation to build the

studio as state-of-the-art as possible. Everything was carefully planned. I

was given enough money to buy a large press, heavy duty aluminum frames, exposure

unit, large drying racks, and various necessities. I had to improvise on the

rest.

The vacuum exposure frame was made out of a sliding glass door, wet suit rubber

blanket, attached to a vacuum motor, and hung from the wall with garage door

opener tracks. This allowed me to slide it into a vertical or horizontal position,

as needed.

I built a simple blade sharpening setup, using a washing machine motor and a

wide grinding wheel, to sharpen as many as four smaller squeegee blades for

each run of as many as ten colors. The process of sharpening them all together

was imperative and vital for holding registration. Finally, I built a light

table that would allow me to work efficiently for the endless hours that I would

spend intricately painting, washing out, and repainting block-out into the incredibly

elaborate stencils burnt into the 4' x 5' frames.

When the paper arrived from France I got worried. Before me stood a nine foot

stack of 30x44” Rives BFK: The best printmaking paper available. What had

I gotten myself into?

As soon as the studio was complete I began running tests. Over a six month period

I ran hundreds of tests for exposure times, stencil and screen tolerances, inks

and additives, block-outs, washout techniques, different inks and additives.

Sandra wanted to have the broadest range of colors possible and the results

had to be scratch-proof and fade resistant. She demanded endless testing of

everything. During any given time I had dozens of ink tests sitting on the roof

baking in the hot Arizona sun. These tests proved invaluable when production

finally began, and after thirty years the prints have held their brilliant luminosity.

During the first year I tried, hundreds of times, to print multiple blends on

each run. Printing multiple colors at one time was one thing. But printing multiple

colors all at once that had to blend, physically, on the press, with it's adjacent

color, and then, also had to print at that exact spot on the paper for each

run of 315 sheets proved to be literally impossible. I felt like a juggler who

had to juggle different colored pudding to create new colors.

I invented a simple piece of hardware, which I called a blending wing in the

eleventh month. The success of these wings made the project possible, for the

first time, and they sped up production greatly. I was now able to print all

of the colors and to hold the blends in place for the whole run! But, still,

the hours required of me became endless.

I was now at twelve months into production and under great pressure by Sandra

to work longer hours and at faster speeds. She was obsessed with pushing the

techniques, that I had created, to their limits. Nothing like this had ever

been done, yet she seemed rarely satisfied with my results. I was greatly frustrated

and began to feel inadequate as a printmaker.

During summer, the heat was at least 100 degrees in the daytime. I would get

up at midnight, arrive at the studio shortly thereafter; to expose, washout,

dry and then to block-out all of the parts of the image not needed for the next

run. I had printed master “blueprints” on large sheets of newsprint

that Sandra would draw on, showing, in exact detail, what I would print next,

with PMS color swatches for each color that I had to mix and, finally, pencil

lines showing where each blend would break. Block-out was very detailed, tedious

and allowed no room for errors- too much or too little were not acceptable and,

if any ink leaked, it would ruin the print.

I would finish painting in the block-out in four to eight hours and, while it

dried, I would mix the inks and additives. All ink was weighed, to a tenth gram,

if necessary. I would then set up the press, sharpen the squeegee blades, add

the inks and, finally, pull a printers proof for Sandra. Tweaking the colors

was a very important process and always took between three and eight hours.

Every adjustment of color would have to be reproofed and re-evaluated.

Because of the oppressive heat, I had to wait until the temperature dropped

to the low 80's to avoid ink drying on the press. This meant starting my press

runs at about 4 in the morning. The average run took another five to eight hours,

and finally clean up. I could now rest, but not for more than six hours. It

was then back to the studio to start the process all over again.

In between all of these tasks were a myriad of other necessary chores. Cleanup

and collating the prints in production were always important. I had to wrap

the prints in plastic to protect them from sudden shifts in humidity that occurred

with any change in the weather. During the monsoon season I would watch the

hygrometer soar from 8% to 85% in an hour. I greatly feared loss of registration

because of sudden fluctuations in heat and humidity.

My work weeks averaged eighty hours and, during the second summer, I started

to put in over a hundred hours a week. Sandra was beginning to talk about an

article that she had read that said we might be able work without sleep. I new

that she was losing it. Because I worked by myself, I could only get a day off

every 4 to 8 weeks and my personal life had become non existent.

My girl friend left and what few friends I still had evaporated. Sandra became

very paranoid. She thought everybody was a spy trying to steal my techniques.

Even the UPS delivery man, who brought me my inks and other materials needed

for production, wasn't above suspicion. I became very depressed and myopic in

my tiny world, in a studio that had no windows, working for an artist who had

gone insane. I was helplessly torn between all of this craziness and the utter

beauty that I was creating. I had become so obsessed that, like an addiction

to some intoxicating drug, I just couldn't let go.

At twenty months into the project I finally broke down. I walked away from the

studio in the middle of a run. I checked into the Psych Ward of the veteran's

hospital, broken, exhausted and finished. After two days, Sandra and her husband

found me at the hospital. They wanted me to check myself out of the ward and

get back to work. I told them that I couldn't go any further and, when they

told me that I'd lose credit for printing the Journey, I still chose to quit.

I couldn't imagine returning and continuing what I'd done almost everyday for

over a year and a half, by myself. Climbing Mt. Everest would have been preferable.

At least it was outdoors!

The next day the returned to the hospital and offered to hire an assistant for

me, if I'd return and finish the project. For the first time, ever, they acknowledged

that, if they lost me as the printer, the Journey was through being printed.